|

PREFACE: In 2002 I read about Seattlite Susie Stevens, an advocate for

public and "alternative" transportation, who was killed when she was

run over by a bus. Quite the ironic way to go, sort of like an

opponent of leash laws being mauled by a pack of run-away pets.

My left leg had been hurting since my last long run eight days before and I had essentially not done any running since. I was hoping the eight-day rest, and the morning walk to the bus, would remove any trace of pain in my leg. Such was not the case. My left calf had persistent tightness which I couldn't shake, effectively a permanent cramp. Oh well. Nothing to do about it at that point but soldier on. I ran into fellow Pullman runner John Chapman in line for the bus -- no small feat considering nearly 20,000 people were boarding these buses. John was relaxed and in good spirits despite the fact that he was also nursing an injury, one which had kept him from running for the past three weeks. The Pullman contingent was not exactly in top form.

Despite being on the turnpike, the bus ride took an incredibly long time. John and I were convinced the driver was lost or playing some sort of cruel hoax, but if he was, so were all the other drivers in the long line of buses in front of and behind us. Driving from the finish to the start of a point-to-point 26.2-mile race probably isn't the best way to relax, but it is undoubtedly more relaxing than running to the start which is exactly what Pam Reed did. Three weeks prior to the race this 44-year-old woman ran 300 non-stop miles. She then ran the London marathon the day before the Boston marathon, flew to Boston, started at the finish line, ran to the start, then turned around and ran the marathon. I think we're not the same species. We eventually arrived in Hopkinton and then had a few hours to kill at the makeshift athletes' village. As I entered the "village," basically a field with porta-potties, tents, and a stage, a lone guitarist was on stage repeatedly crooning "Sending out an SOS" from the Police's song Message in Bottle. Not yet buddy -- no need for SOS's. I'm feeling fine except for this questionable left leg. It was sunny and warm. I grabbed a couple of bagels and a couple cups of Gatorade and headed into the shade of a tent. Runners were sprawled everywhere, but I managed to wedge myself between prone bodies and three trash cans. I lay there, relaxed and comfortable. My one concern was when I should head to the bathroom. Two hours and 15 minutes before the race I decided to brave the lines and the sunshine. The lines were long and not moving very quickly but as I was in no hurry, that was fine. I had time to do some people watching.

In 2002 Cynthia Lucero defended her Ph.D. dissertation on the topic of how running marathons helps runners grieve for ailing family members or lost loved ones. The subject of Cynthia's work was pervasive in the athletes' village. I saw many shirts with pictures of missing loved ones for whom the runner was doing the marathon. Some of those being remembered were victims of September 11th (identified by 9-11-01 beneath their picture), some were victims of cancer, and some were simply identified as being no longer with us. There were many "teams," too. The purple shirts of the Leukemia Society's Team in Training were sprinkled throughout the crowd. Many police, firefighters, and soldiers wore apparel stating their affiliation or announcing missing comrades. After doing my business in the porta-potty I went back to the tent to put on sunscreen. Space was tight, but I found a vacant strip adjacent to some tables where I could set my bag and cover myself in SPF 30. While there, a woman parked herself a short distance away. She started frantically rummaging through her race bag. She was agitated to the point of shaking. Since I had stocked my bag with a wide variety of contingency items (sunscreen, various snacks, salt tablets, Vaseline, etc.), I thought I should ask if I could help her. Right when I was about to offer my services, she up-ended her bag, reached into the pile, pulled out a tampon, and held it up in the air. Search over! She turned to a woman next to her (obviously a total stranger but one who had noticed her panic) and said, "Of all mornings! Now where am I supposed to put this?" (I'm assuming she was rhetorically asking about placement of the tampon while running and before use and was not seeking guidance as to its proper usage.) Perhaps best that I didn't get a chance to offer help. Images of Uta Pippig winning the 1996 Boston Marathon covered in feces and menstrual blood sprang to mind. With my new coating of sunscreen I decided to get back in line for the toilets. Something to do while passing the time -- a great place for people watching. Young and old. I saw a man with a T-shirt which said "The Dad" and next to him was "The Daughter." Muscular and hulking, thin and wiry. Short and tall. But all fit. Most of the athletes were white, probably followed a distant second by Asians (the elite runners were nowhere in sight so I didn't see a cluster of East Africans). While in line, an announcement was made that I could depart the village and head to the start line -- I and 8000 other runners whose bib numbers fell within a certain range. On the half-mile walk to the start we passed buses where we dropped off our race bags (to be reclaimed at the finish). The registration booklet sent to the runners a couple weeks before the race spelled out the timing of activities and where everything would be stationed (bathrooms, buses, water tables, etc.). This booklet also emphasized that one should not relieve him/herself in public. If one did, the guilty party would face disqualification from the race (if a race official caught them) or worse (if the police caught them). It seems not everybody bothered reading the booklet or perhaps they didn't take the warning to heart. I heard some yelling off to the side and saw a police officer chasing a gentleman out of the bushes. Oops! As you might suspect, the would-be marathoner was more fleet of foot than the officer, but I saw the officer writing something down. I recall once seeing an announcement in my parents' assisted-living facility for a talk entitled, "Who's the boss, you or your bladder?" (Shame that I didn't get a chance to attend -- I've been pondering the question since.) If this officer was writing down the runner's bib number, there is at least one runner whose official "DNF" at the 2005 Boston Marathon is evidence of the bladder as boss. About 100 yards away from the starting line I noticed some more porta-potties. What the heck. I didn't really have to go, but the start of the race was still 25 minutes away and I didn't want to be faced with any issues out on the course. I hopped in line and had my turn with about 10 minutes to spare (all the while repeating the mantra: I'm the boss, I'm the boss!). I was 100 yards from the starting line, but I was not 100 yards from where I was supposed to start. Runners are seeded according to their qualifying time. I was in corral 8, as were 1000 other runners. I had a little walk from the toilet to my corral. When I got there, the corral was packed -- people spilling out onto the sidewalk. We were supposed to enter the corral from the back. I managed to squeeze in with about two minutes to go before the official start of the race. I had no concerns about starting at the back of the pack. I wanted to go out easy. Additionally, the finishing time was really based on the computer chip, worn on my shoe, which would tell precisely when I crossed the start line. My calf was still tight, but not a major concern. It was hot waiting for the start. A bright sun with no shade. Bodies tightly packed. Fortunately I didn't have long to wait. The start! Oh, wait, never-mind. Everyone made a surge forward and then abruptly stopped. Sort of like everybody in a line of cars moving when the traffic light turns green but then realizing they aren't going anywhere until the car in front moves. We started walking. No. Stop. Walk again. Jog. Back to a walk. This acceleration and deceleration continued for awhile with the average speed steadily picking up. I finally crossed the start line six and a half minutes after the official start. By the time I crossed the start line, the pack had thinned to the point where I could run at a decent clip. It was slower than the pace I was hoping ultimately to maintain, but there was plenty of time and distance to average things out. The spectating crowd at the start was surprisingly large. I had never seen a turn-out like this for a race. People were perhaps five or six deep along both sides of the street, and they were loud! What were they yelling? Mostly the names of the women who had adorned themselves with their names. Ah, that explains it. "Keep it up, Amber!" "Go, Beth!" "Looking good, Charlene!" And on and on. You would think someone in the crowd would have thrown in a "Go, John!" every once in awhile, secure in the knowledge that it is almost impossible to not have a John in a crowd of men. From the start of the race my calf felt tight and it kept growing progressively tighter. I kept to my original pace, hoping things would loosen up. We got to the 5 km mark at which point they had timing mats to record our splits. Allegedly this would be immediately put on the Web and Shira could check out how I was doing. Just past the 5 km mark, not more than 50 m beyond, it happened. Something popped in my left calf. I'm sure you've seen people running who have suddenly pulled up lame (as Maurice Greene and Michael Johnson both did in the 2000 Olympic trials for the 200 m) -- comical in a way. The affected leg jumps up and acts as if there is suddenly a bed of hot coals beneath it. My leg didn't want me to put any pressure on it. Thankfully this happened at a narrow section of the road with a rather steep drop-off to either side, i.e., there wasn't a crowd around. In a foolish attempt to get my leg back in action, I hobbled to the side of the road and stretched. It was clear that stretching wasn't going to do anything so I started to walk. The registration booklet claimed that at the water tables there would be buses to pick up drop-outs. Water tables were approximately every mile. I didn't want to go backward on the course so I started to walk to get to the next water table. It hurt like hell just to walk. But, hey, if it hurts to walk, you may as well run, right? I began running again -- if you could call it running. It was more like a bobbing hobble. The pain was intense enough that I developed a sort of tunnel vision. I was in a fog and just wanted to get off the course. I was dully aware that the crowds were back along the side of the road (Amber! Beth! Charlene!) and that everybody was passing me. All my corral-mates were sweeping past me and those who had been in corrals behind me didn't stop to chat as they blew past. I made it to the water table and didn't see any sign of a bus or of anybody above the rank of fluid distributor. Bummer. I didn't want to wander around asking about how to drop out at the four-mile mark of a marathon. There was too much shame in that. I just wanted to hobble directly onto a bus and call it a day. The lack of an obvious exit dictated that I keep going and hope for better luck at the next water table. Mile five and essentially the same story. No bus. My hobbling was painful but my pace was fairly steady (slow, certainly, but steady) and the pain wasn't escalating. Perhaps endorphins were kicking in. On my way to mile six I caught sight of a shapely woman passing on my right. She had "Team Nice Ass" emblazoned across her bun-hugger shorts. Surely there is a potential psychology Ph.D. dissertation for anyone interested in investigating the motives of this running team. (I googled "Team Nice Ass" but with such a search-field google doesn't want to produce hits related to marathons.) Ms. Nice Ass must not have advertised her anatomy on the front because I didn't hear cheers of "Keep it up, Nice Ass!" Being passed by Ms. Nice Ass helped to lift my mental fog a bit, but not so much that I could find a bus at mile six. Off to mile seven. With the lifting of the brain fog came the realization that it was rather warm. In the pre-race material sent to the runners there was a pamphlet on proper hydration for a marathon. Interestingly, it went on at some length about overhydration, i.e., hyponatremia, where the body develops a dangerously low level of sodium. I had some salt tablets in my pocket and made a point of taking a couple at the next, bus-less, water table. On I went.

At one point I had the misfortune of running near a gentleman who was wearing a Yankees' shirt. What was this guy thinking? "Yankees suck! Yankees suck!" A million people yelling at him, over and over, that the thing with which he chose to affiliate sucked. Maybe Yankees' fans thrive on that, but the negativity kept my mind from settling into a happy place. I was glad when we drifted apart and the wrath of the Red Sox fans was no longer in evidence. (Amber! Beth! Charlene!) I eventually got to the half-way point -- the "Wellesley half." Gene Allwine, a Boston-Marathon veteran, had called the night before the race to wish me luck. He mentioned the run past Wellesley College, clearly one of the high-points of the race for him. Gene's description of cheering co-eds didn't prepare me for this. The roar was unbelievable. This was damage-your-eardrums kind of loud. The students were separated from the runners by barricades lining the road. They were draped over the barricades as if their favorite rock star were just on the other side. Again, unbelievable. What motivated them to show such exuberance is truly beyond me, but perhaps that kind of vitality is required to get into what is arguably the best women's college in the country. Hobble and hydrate, hobble and hydrate. There was a brief period where my bladder was hinting that it might like to visit a toilet, but I maintained my authority. Actually I think the heat was such that, despite all I was drinking, I was becoming a bit dehydrated (it would be about seven hours after the start of the race before the bathroom became a necessity).

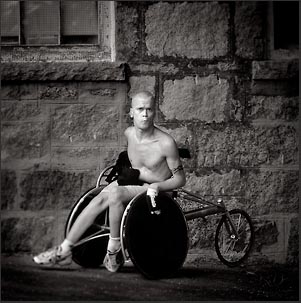

I later learned the gentleman in the wheelchair was Jason Pisano. He was born with cerebral palsy and has participated in a number of races (he is a veteran of the Boston Marathon). I found a portrait of Jason by Derek Dudek on the Web. I think it would be great to have a copy for my office -- inspire me to get through the marathon of my work day. Maybe for Christmas I'll treat myself.

Shortly after passing Jason I came to "Heartbreak Hill" -- the storied hill that is supposed to test the metal of a marathoner. Had I been running faster, the hill may have been more of a test, but at my pace it wasn't much of a challenge. The remainder of the race was, literally and figuratively, all downhill. I was keeping up with my neighbors and even passing some people. Around mile 24 I passed a woman I had been running behind during the first 5 km of the race. Woo hoo! Go, me.

Beyond the finish line I saw several instances where body fluid wasn't where it was supposed to be. Since the Boston Marathon is the granddaddy of marathons, runners feel compelled to push themselves, resulting in plenty of spent bodies at the finish. Vomit puddles were scattered about and I watched more than one runner generate another puddle. This spewocity and vomitus upthrow was taking place right by the school buses which carried our race bags back from the start. Hey! Body fluid cleanup kits! Naw, clearly this was a lost cause. Besides the vomiters, people were being carted off in wheelchairs (i.e., people who hadn't started the race in wheelchairs), and I saw one person passed out on the sidewalk. Perhaps they hadn't read the pamphlet on proper marathon hydration? Whatever the case, I actually felt great (other than the hurting leg). This was the slowest (non-Ironman) marathon I've done: 3:41:36 (average pace of 8:27/mile). That's essentially the pace of a long training run, so I didn't have an excuse to make a puddle or to get a ride in a wheelchair. I did, however, pamper myself with a taxi ride back to Jim's place. Pamper? Well, not exactly. The second I sat down in the back of the cab my left leg seized up in a horrible cramp. Ouch! I thought of asking the driver to stop and let me out. Fortunately there was enough room in the back to allow me to pick up my leg and stretch it across the seat. I didn't learn of Cynthia Lucero and her dissertation on what motivates grieving marathons until after the race. Cynthia Lucero defended her dissertation in April of 2002. Her parents came from Ecuador to attend her defense and to help her celebrate. Part of the festivities, and something of the capstone of her work, was Cynthia running the Boston Marathon. True to her dissertation, she was running the race as part of the Team in Training, thus raising money for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. She made it to mile 20, collapsed, and died. Tragic. Cynthia had complained of feeling dehydrated prior to her collapse, but she actually died of hyponatremia -- overhydration. The reason we were all sent pamphlets on proper hydration was a direct result of Cynthia's death. From what I read, Cynthia was a pretty amazing woman and she lives on in several ways. An article I read in the Boston Globe talked specifically about the seven people who had received organ or tissue transplants from Cynthia. Her sister has set up a Web site in remembrance of Cynthia.

|